EECAR-TR Ecology of plant and animal communities

Research theme - Ecology of plant and animal communities

In the ecology of plant and animal communities, our research aims to gain a better understanding of the assembly rules and coexistence processes that explain the high level of biodiversity in Mediterranean ecosystems and the factors behind the very low resilience of these communities following human disturbance, in particular through historical ecology approaches, including in particular the study of viable soil seed banks, the true seminal memory of plant communities. The vast majority of our approaches are experimental and linked to concrete ecological restoration operations that allow us to manipulate in situ and on a large scale of abiotic and biotic variables. They are also carried out ex situIn this way, we can better understand the specific causal links between plants and plants or arthropods and plants.

Example of recent research - Impact of the colonisation of grazing lands by exotic black pines on pollinators

What is the impact on pollinators of the colonisation of the pastoral grazing lands of the Causse Méjean by pine trees?

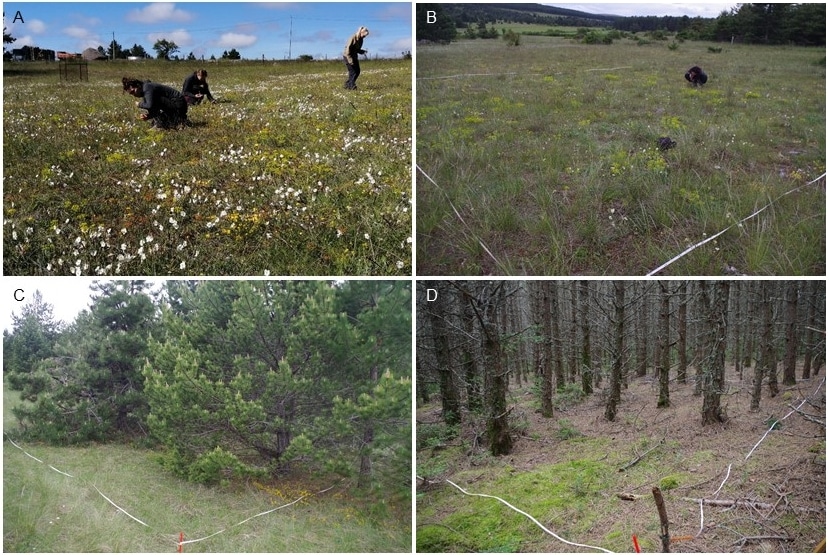

In many regions, pine monocultures are replacing open ecosystems, profoundly transforming them. The increase in tree cover affects the diversity of herbaceous plants and has major repercussions for insects, particularly pollinators. In this context, the main objective of this study is to understand how the colonisation of lawns by pine trees from Pinus nigra affects biodiversity and pollination. To do this, we studied 12 sites on the Causse Méjean, each with an area of Mediterranean mountain steppe (EUNIS code E1.51), a plantation and two areas of steppe more (>50% pine cover) or less (<50%) colonised by pines.

We found that the herbaceous cover decreases with increasing tree cover, and the same pattern was observed for the richness and frequency of herbaceous plant species, as well as for the richness and abundance of plant-pollinator interactions. The composition of herbaceous species is similar in the steppe and colonised areas, and only different in the plantations. Different insect groups have different sensitivities to increasing tree cover: plant-fly, -syrphid and -ant interactions are more numerous in lawns than in plantations (and intermediate in colonised areas). Interactions between plants and hoverflies and honey bees also diminish with colonisation and these groups are absent from the plantations. Wild bees and beetles do not appear to be sensitive to variations in tree cover. While it is already well known that pine plantations should be avoided in open ecosystems, our results underline that the colonisation of these pines outside plantations must be absolutely controlled. Although tree cover has little impact on the plant composition of steppe communities in the short term, it does have a significant effect on plant-pollinator interactions.

Example of recent research - Is the human footprint on plant communities indelible?

Human activities are transforming and have transformed plant communities, but for how long will the influence of these disturbances be perceptible even after they have been abandoned?

Measuring the impact of human activity on ecosystems and their long-term consequences is one of the main areas of research in historical ecology. as a complement to palaeoecology. The aim is not only to identify the different types of past disturbance, but also to measure their possible consequences on the functioning of current ecosystems. Plant communities are in fact quite sensitive to very ancient disturbances and may still, in some cases, display specific compositions, richness and diversity today under the influence of past practices that were abandoned thousands of years ago. Thierry Dutoit explains here.

In this way, we measured the impact of the pastoral enclosures that have been present on the Crau plain (south-east France) since Roman times and which have been abandoned over the centuries. Our results showed that these enclosures still influence soil fertility and the composition and richness of current vegetation even after more than 1,500 years of abandonment (link). The persistence of these effects is not linked to the long viability of the seeds of the vegetation of the old enclosures in the soil, but to a very slow evolution of soil fertility linked to a very large input of organic matter when these enclosures were used to concentrate the herds (link).