SANTES Team - Environmental Health and Toxicology

Presentation

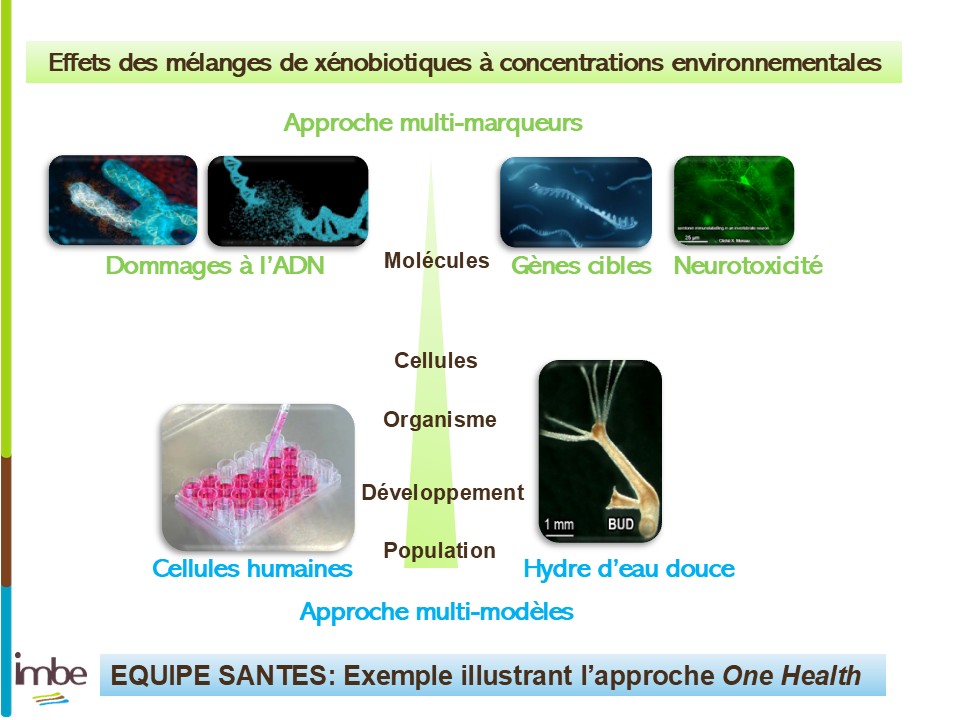

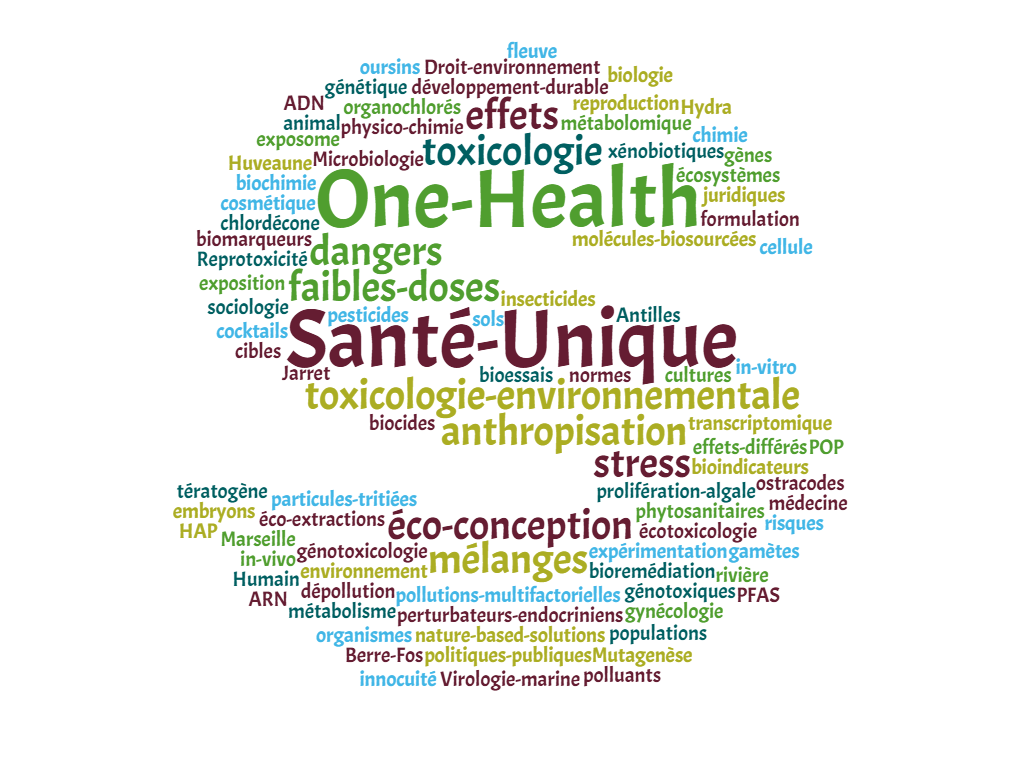

Resolutely interdisciplinary, the SANTES team conducts research that integrates human health and the health of ecosystems using the holistic approach of a Santé Unique (One Health). The team has 21 statutory members, 10 of whom are qualified to supervise research (HDR), supervising work in the field of health ecology, weaving together ecology, biological and medical sciences, and the humanities and social sciences.

In a anthropisation context leading to the emergence of environmental stresses of a chemical, physical or biological nature, all living beings, including human beings, are confronted with a wide range of exhibitionsthroughout their lives, right from the start.

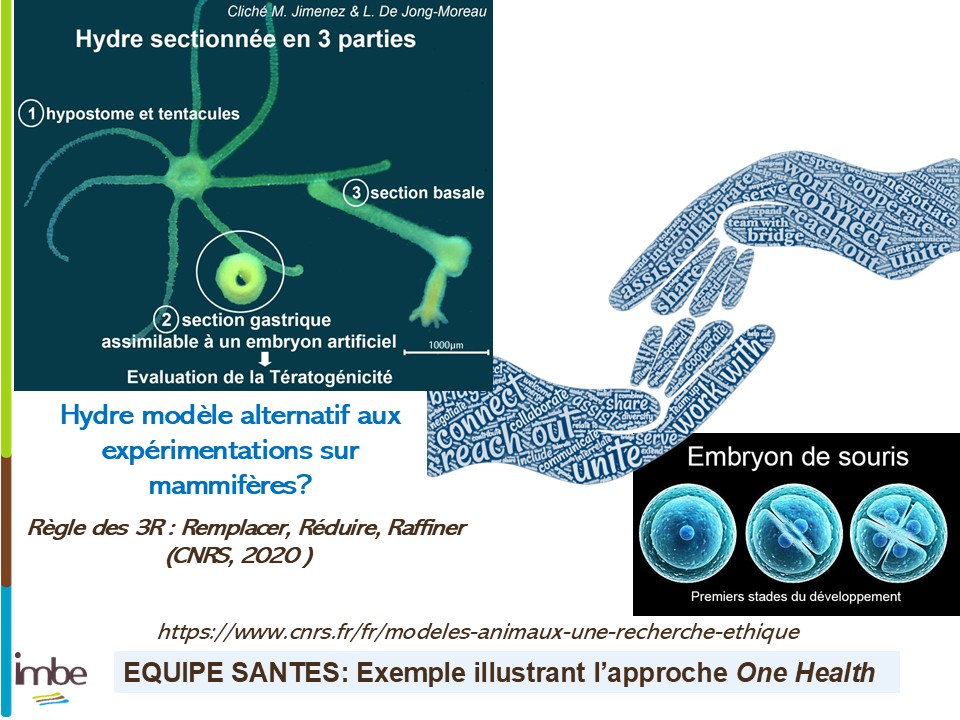

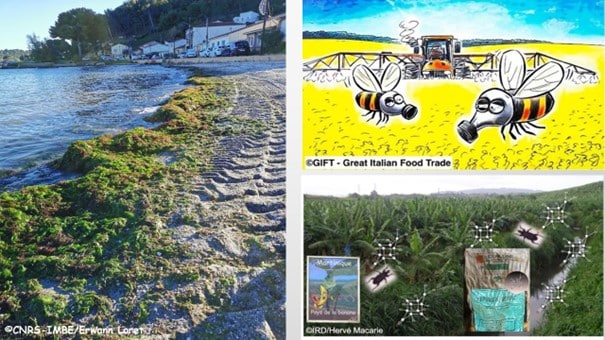

Our objectives are to document the hazards that make up the exposome by assessing, for example, the effects of low doses, delayed effects and the effects of complex mixtures of xenobiotics, particles and radiation on humans and ecosystems. Our approach The overall aim is to identify and characterise hazards, which is an essential prerequisite for defining a preventive approach to exposure-related risks, and to define public policies and legal standards for biocides cocktails. Our approach also involves proposing integrative eco-design strategies, i.e. sustainable and proven developments of biosourced molecules (nature-based solutions) in the field of phytosanitary products and cosmetics. The team is also interested in nature-based solutions for: (i) stemming the accumulation of green algae on coasts, the massive proliferation of which is causing environmental and human health problems, (2) developing bioremediation processes for polluted soils in the French West Indies.

Skills Cell biology, molecular biology, health, environmental law, ecotoxicology, genotoxicology, microbiology, mutagenesis, physical chemistry of formulation, environmental toxicology, synthesis of biomolecules, virology

Research topics

The Team

Collaborations

Impacts of tritiated dust (Horizon Europe TITANS project)

- Pollution by the organochlorine insecticide Chlordecone in the French West Indies (ANR LICOCO project),

- Deployment of an efficient, acceptable and operational soil treatment method to reduce exposure to chlordecone and its degradation products (ANR DéMETER project),

- Chemical and toxicological characterisation of organic species emitted by fumes from road materials incorporating asphalt aggregates (ADEME EDIFIERS project),

- Controlling green algal blooms Ulva lactuca in Brittany using a virus naturally present on the coasts of Provence (ANR VIMCAV project),

- Preventing exposure to reprotoxic environments for couples involved in a fertilisation process in vitro (AP-HM PREVENIR-FIV clinical trials),

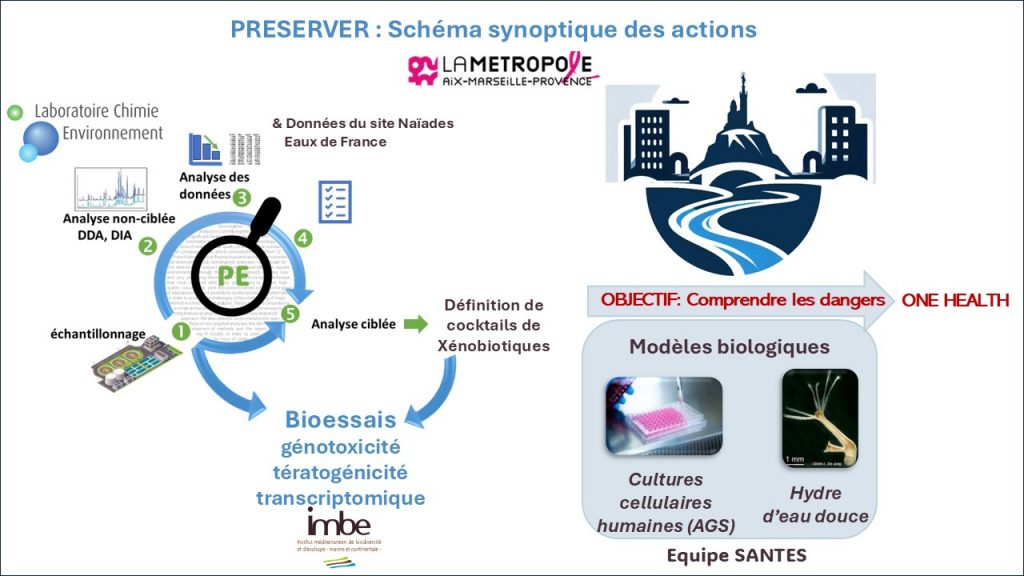

- Characterisation of the effects on living organisms of mixtures of endocrine disruptors and other pollutants in the wastewater and rivers of the Aix-Marseille-Provence Metropolitan Area (PRESERVER project),

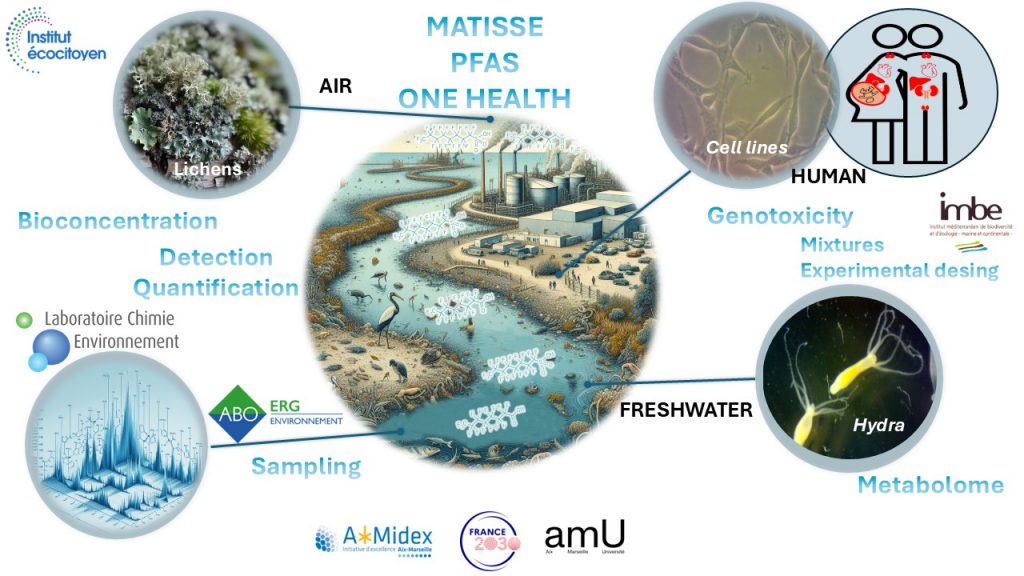

- PFAS contamination in industrial areas using a multi-scale study (Amidex MATISSE project),

- Study of the link between chronic inflammatory skin diseases and environmental pollution (DIAHR clinical trial in collaboration with the Dermato-Oncology, General Dermatology and Venereology Department headed by Professor Marie Aleth RICHARD and the Biogenopôle Centre headed by Bruno LACARELLE at APHM, Hôpital de la Timone, and the Alphényx company,

- Optimisation of cosmetic formulations and food supplements using nature-based solutions (Partnerships with ORUS Pharma & Stratagène).

Socio-economic partners

ABIAER (Asociación de Biotecnología e Ingeniería Ambiental y Energía Renovable, Mexico, https://abiaer.com/)

Azur Isotopes (Marseille, France)

ABO-ERG Environnement (Vitrolles, France)

Eight lives" associations (St Chamas Etang de Berre, France)

GIPREB (Etang de Berre, France)

Institut Ecocitoyen pour la Connaissance des Pollutions (Fos-sur-Mer, France)

Istres Town Hall (Etang de Berre, France)

Metropole Aix Marseille Provence (Marseille, France)

St Brieuc metropolitan area (France)

VIRALGA (SME ST Brieuc, France)

Academic players

Geological and Mining Research Bureau (Orléans, France)

Caribbean Agro-Environmental Campus (CAEC, Martinique, France)

IMIDRA (Instituto Madrileño de Investigacón y Desarrollo Rural, Agrario y Alimentario, Madrid, Spain, https://www.comunidad.madrid/centros/finca-encin-alcala-henares)

Institute of Neurophysiopathology (UMR7051, Aix Marseille University, France)

Environmental Chemistry Laboratory (UMR 7376-Aix Marseille University, France)

Caribbean Social Sciences Laboratory (UMR CNRS 8053, University of the West Indies, France)

Mountain Ecosystems and Societies Laboratory (Grenoble Alpes University, France)

Laboratoire d'Études et de Recherches Appliquées en Sciences Sociales (EA 827, Toulouse Paul Sabatier University, France)

Materials and Molecules in Aggressive Environments Laboratory (Université des Antilles, France)

TGML platform (TAGC U1090, Aix Marseille University, France)

Stella Mare platform (UMS3514, Université Pascal Paoli, France)

University of Western Brittany (Brest, France)

Cartage University (Tunisia)

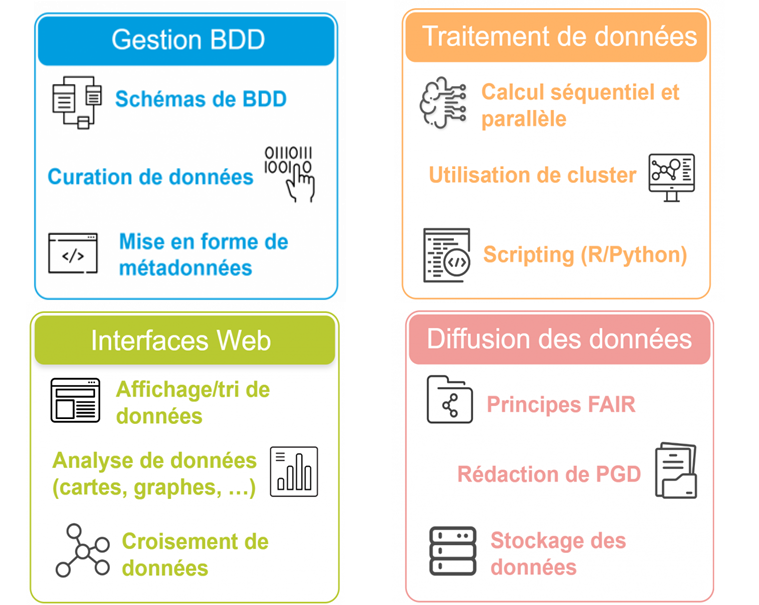

No information